“How easy life is for those who give grand names to their trivial pursuits and passions, presenting them to humanity as monumental deeds for its benefit and prosperity.” - Goethe, The Sorrows of Young Werther

Doctor of Philosophy Igor Chubais has proposed a fascinating idea: to establish a new academic subject called “Russian Studies” in the Russian education system. This subject, according to an article in Mir Novostei, would cover Russia’s history, culture, geography, and more. The concept seems excellent—people need to know their country’s history. But the question is, can we create a truthful and unbiased textbook for Russian Studies?

It seems unlikely that in the next 30-40 years, an impartial history textbook could exist, free from ideological influence. Some historians still cling to Marxism-Leninism, while others view the Soviet era in only the darkest terms. For example, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, introduced into the curriculum at the request of Solzhenitsyn’s widow, was impactful when first read in the 1960s. Yet other works, like Bas-Relief on the Cliff, which described the tragedy of a sculptor forced to carve Stalin’s image, also capture the harsh realities of that era. Knowing the darker sides of history is essential, but should they alone define a generation’s perspective?

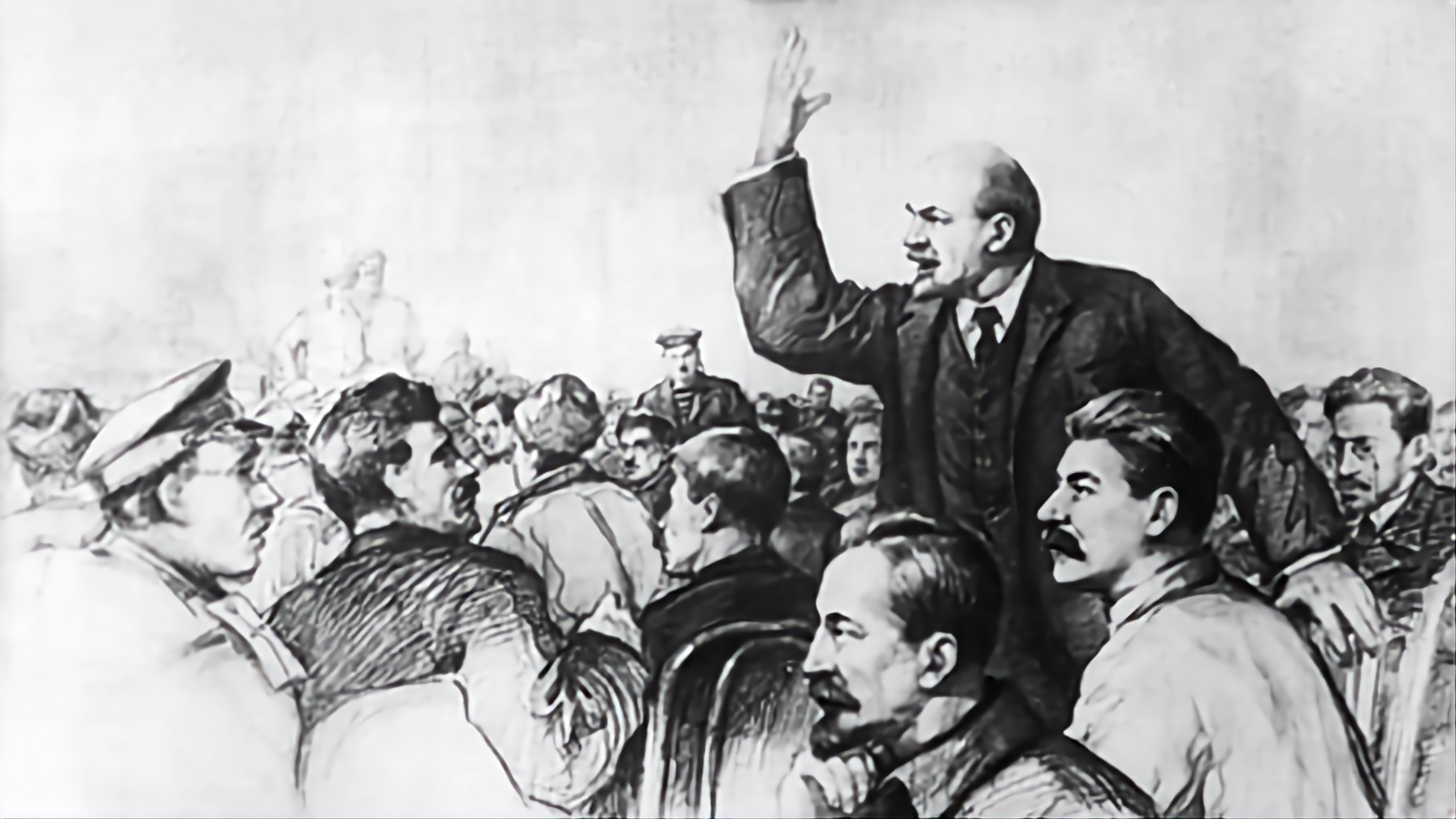

**A Balanced Perspective on Soviet History ** It’s essential to remember the positive achievements of the Soviet era, alongside its dark aspects. Figures like locomotive driver Krivonosov, pilot Chkalov, and others made valuable contributions. Despite severe hardships, the Soviet people built a strong industrial base, enabling the country to withstand the struggles of World War II. Such resilience deserves to be part of the historical narrative. To suggest that the Soviet period should be erased, as Chubais proposes, is simply unrealistic. History should be complete, encompassing all shades of the past.

National Pride and Patriotism in Historical Education

It’s misleading to imply that pre-revolutionary Russia was a paradise. Authors like Gogol, Chekhov, and Leskov reveal the struggles of ordinary people in the 19th century, which were far from idyllic. A hungry, oppressed population doesn’t rebel without cause. The Soviet government eventually collapsed in 1991, unable to meet people’s needs. Therefore, instead of erasing the Soviet period, we should study it deeply, acknowledging both the achievements and mistakes, to give young people a well-rounded view.

Patriotism Beyond Political Systems

Chubais argues that one can’t be a patriot of both North and South Korea, using this to claim that patriotism for both Russia and the USSR is contradictory. But a nation is loved not for its political system, but for its people and land. True patriotism should inspire pride in our heritage and appreciation for the sacrifices of past generations. To instill pride in young people, we must teach them about their forefathers’ achievements without reducing our history to mere political disputes.

In short, a national idea based on a well-rounded, honest portrayal of history—both the hardships and the triumphs—is key to fostering genuine patriotism.

As a lib in high school, I remember reading ODitLoID and feeling very enthusiastic about the mission of the gulag. Buinovsky was unironically my favorite.