When the MeToo movement took off across the globe in 2017, it changed how we think about artists and their art.

As victims of sexual harassment and assault spoke out, the public became more aware of the behaviour of well-known people, including successful artists. Audiences immediately began to view these artists’ work through the lens of their actions.

As a result, many of our favourite books, songs and art works became irrevocably tainted by the transgressions of their creators.

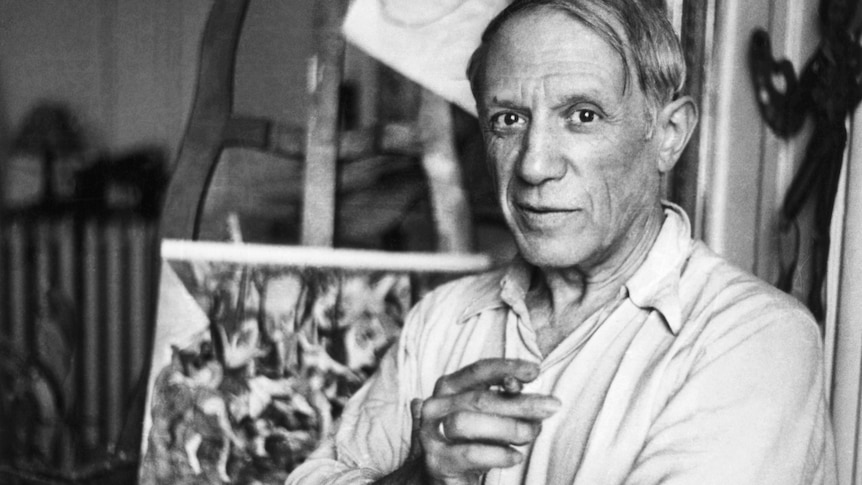

Admiring the work of Pablo Picasso — the cubist artist who burned his partner Françoise Gilot’s face with a cigarette (and painted it) — or Alfred Hitchcock — the film director who tried to destroy actress Tippi Hedren’s career when she rebuffed his advances — became a less straightforward proposition.

“In the aftermath [of MeToo], people were left wondering what to do about their heroes,” US critic Claire Dederer writes in her new book, Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma.

I would argue that while yes, they were recognized as atrocities, there was still a common expectation that massacres could and would happen during wartime. As a result of this general expectation, the Khan was never really looked at in any different light from those Assyrians you mentioned.

Hitler, however, behaved quite differently from his contemporaries. Only Stalin was quite that bloody. This illustrates a clear difference of the changing standards of the time, further reinforced by things like mass literacy and rapid communication of news.

To say that humans haven’t changed requires ignoring a great deal of relative peace and prosperity. While we will likely never be done 100% completely with atrocities of different natures, simply reducing how common they are is an accomplishment that should not be ignored.