- cross-posted to:

- askscience@lemmy.world

- til@lemmy.world

- cross-posted to:

- askscience@lemmy.world

- til@lemmy.world

cross-posted from: https://lemmy.world/post/6080744

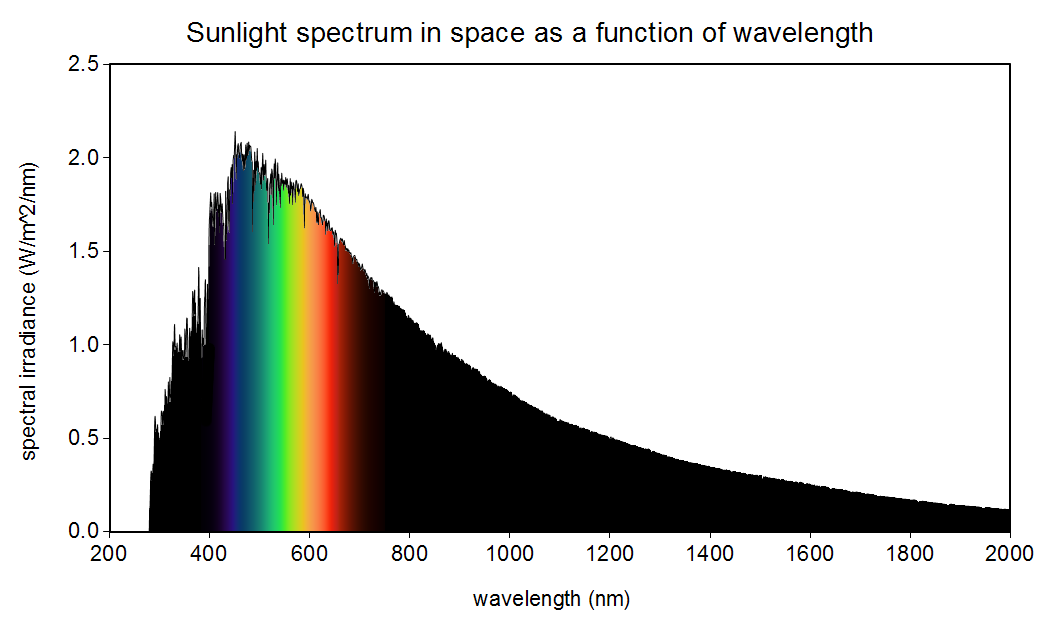

The sun is not yellow or orange as we see in books and movies. It emits all the colours in the visible spectrum (also in other spectrums as well) making it white!

https://www.scielo.br/j/rbef/a/mYqvM4Qc3KLmmfFRqMbCzhB/?lang=en

This is something that bothered me when I was in undergrad but now I've come to understand. The article above goes through the math of computing different Wien peaks for different representations of the spectral energy density.

In short, the Wien peaks are different because what the density function measures in a given parametrization is different. In frequency space the function measures the energy radiated in a small interval [f, f + df] while in wavelength space it measure the energy radiated in an interval [λ, λ + dλ]. The function in these spaces will be different to account for the different amounts of energy radiated in these intervals, and as such the peaks are different too.

(I typed this on a phone kinda rushed so I could clarify it if you'd like)

Hey thanks for the reply! I'll admit that paper lost me pretty quickly, so I am probably missing a subtle point. But it feels deeply unintuitive since frequency and wavelength are just two different ways of describing the same physical quantity.

So if I have a given source of photons, how the heck does the color of photons delivering most cumulative power change whether I choose to describe that color based on its wavelength or it's frequency?

Is there an analogue to something like sound energy or is this quantum physics weirdness?

(These are semi rhetorical questions… I'm not expecting you to explain unless you really feel like it 😀)

So we can see the where this weirdness comes from when we look at the energy for a photon, E=hf=hc/λ

When we integrate we sort of slice the function in fixed intervals, what i called above df and dλ. So let's see what is the difference in energy when our frequency interval is, for example, 1000 Hz, and use a concrete example with 100 Hz and 1100 Hz. Then ΔE = E(1100 Hz) - E(100 Hz) = h·(1100 Hz - 100 Hz) = h·(1000 Hz) = 6.626×10^-31 joules. You can check that this difference in energy will be the same if we had used any other frequencies as long as they had been 1000 Hz apart.

Now let's do the same with a fixed interval in wavelength. We'll use 1000 nm and start at 100 nm. Then ΔE = E(100 nm) - E(1100 nm) = hc·(1/(100 nm)-1/(1100 nm)) = 1.806×10^-18 joules. This energy corresponds to a frequency interval of 2.725×10^15 hertz. Now let's do one more step. ΔE = E(1100 nm) - E(2100 nm) = 8.599×10^-20 joules, which corresponds to a frequency interval of 1.298×10^14 hertz.

So the energy emitted in a fixed frequency interval is not comparable to the energy emitted in a wavelength interval. To account for this the very function that is being integrated has to be different, as in the end what's relevant is the result of the integral: the total energy radiated. This result has to be the same independent of the variable we use to integrate. That's why the peaks in frequency are different to those in wavelength: the peaks depend on the function, and the functions aren't the same.